Buttery. Briny. Bright. Creamy. Sweet. Nutty.

I am thinking about the flavors rolling over my tongue as I gently chew the oyster, swirl its liquor. What do I taste? Is it cucumber? Melon?

It’s more a sensory experience that mimics the singular beauty of kneeling in the surf and taking one of those rogue waves to the face. It’s an explosion of ocean. Quintessential Florida, right there on the half-shell.

Oysters and clams have been part of the Floridian culinary experience for eons, but in recent years that experience has morphed from what once flooded out of the now-healing Apalachicola fishery into one that’s increasingly boutique—helmed not by fishermen, but farmers.

Florida shellfish aquaculture has only been around a few decades, but in recent years has exploded in areas like Panacea, south of Tallahassee, where fancifully named oysters are making major inroads in high-level eateries. And something like 90% of Florida clams are farmed in Cedar Key.

But things are getting even more local.

A growing number of Tampa Bay’s top tables and markets are stocking products like the white-shelled clams of Two Docks Shellfish, which harvests its bivalves within sight of the Sunshine Skyway and whose oyster leases, acquired a few years back, are just now starting to produce.

“Cedar Key is still the center of gravity when it comes to clams,” says Two Docks’ Aaron Welch III. “And places around the panhandle have gotten serious quickly about oysters, but we make beautiful animals here in Tampa Bay—and unique ones, too.”

Restaurateurs and chefs like Heidi and Michael Butler seek out these upmarket proteins for their menus and adjoining markets.

“I love the [Two Docks] product—it’s the perfect-size clam and it’s very tender,” says Heidi Butler, “captain” of The Helm Provisions & Coastal Fare in St. Pete Beach. “We shuck them raw and do them on the half shell by the dozen. We do them steamed—fresh garlic, white wine, butter, and parsley—with crusty bread on the side. We got through a lot of them.”

Succulence notwithstanding, it’s not the sole reason they’re appealing.

“It’s fresh, it’s local, and customers love this,” says Helm Chef/Owner Michael Butler, who estimates about 80% of their clientele is local, too.

“Customers really care where you’re sourcing,” Heidi explains. “People are a lot more conscientious about what they’re eating and where it’s coming from.”

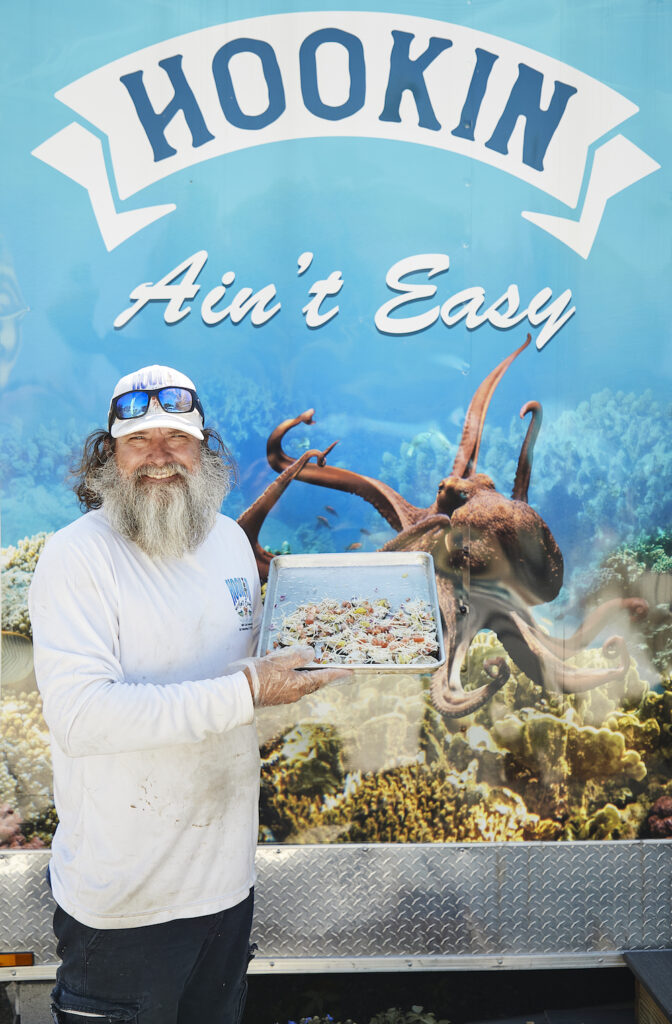

It’s a similar story at Hookin’ Ain’t Easy Seafood Company in St. Petersburg.

With 23 years of commercial fishing experience—blue and stone crab, all manner of fish— South St. Pete native Matthew Neumann used to sell his catch to other markets before he and wife, Veronica, opened their own two years ago.

“Now, we sell it ourselves, but we get it from other people, too,” Veronica says. “Being a small business, a big thing for us is that there aren’t many mom-and-pop places that can thrive in Tampa Bay anymore without the support of other mom-and-pops.”

The Neumanns discovered Two Docks when their neighbor, Two Docks farm manager Marc Scott, popped in to introduce himself. Product that came straight out of Tampa Bay, harvested and delivered the same day—not to mention tasty and beautiful—has built a relationship going on two years.

“Aesthetics matter for both clams and oysters,” says Welch, who’s in the process of moving their Fort Pierce hatchery to waterfront property in nearby Rubonia.

Oysters and clams are raised the same way early on, spawned in the hatchery and reared for a couple of months on land before being moved out onto the farm. But from there, the oysters become high maintenance.

“Clams go on the bottom,” Welch explains. “They want to be buried in the sediment and left to grow.” After that, problems are few. Tonier oysters grow in what’s called the water column—the top 18 inches. Tough spot for a product that needs to stay pretty.

“Algae grows on them. Barnacles grow on them,” Welch says. “And there are other things that can hurt their appearance. You have to pull them out of the water and dry them off so the things that are living on them die.”

Cup size and shape matters, too.

“You have to tumble them,” Welch says, explaining the bingo-cage-like contraption that chips the leading edge of the shells. “This is what forms that beautiful cup that people want to see when they order oysters on the half shell.

Clams just want to be planted. Oysters want to be loved.

Brian Lampe, executive chef for Tampa’s Rooster & the Till is ready to love them.

For its first five years, the restaurant—recently awarded the Bib Gourmand distinction in Florida’s first-ever Michelin Guide selection—focused heavily on a boutique oyster program that featured East and West Coast offerings. Though they’d always source Cedar Key clams, oysters came from out of state.

Lampe’s recent discovery of St. Petersburg–based Lost Coast Oyster Company will likely change that. Lost Coast’s Brian Rosseger harvests his “LoCos” oysters in small numbers out of Terra Ceia Aquatic Preserve.

“I found them while doing my homework for an oyster duo I wanted to feature on a tasting menu,” Lampe explains. “His were beautiful—small cup, super clean.”

Seafoam, says Lampe, was a tasting note. “So, to piggyback on that, we made a foam to top one of them using kombu seaweed, lemon, and some local sea salt that’s also harvested in St. Pete.”

Lost Coast doesn’t produce a level of volume that can supply most restaurants regularly. Instead, Rosseger and his wife sell direct to consumer via pre-order and pickup—or at raw-bar pop-up events at various locations around town. Follow them on social media (Facebook, Instagram) for information or to message about orders.

For Lampe, discovering boutique oysters in Florida required re-education.

“I had that mentality that oysters from warm water weren’t anything I’d ever want to serve. Then I discovered these beautiful little oysters that were farmed less than an hour from here—harvested and brought to the restaurant … and you’re eating it that night?! That’s something in nearly 10 years of being open we’d never provided.”

Veronica Neumann has a customer who comes in for local clams every Friday without fail.

“She gets half a bag, shucked, and eats them raw,” she laughs.

Local oysters aren’t on the Hookin’ Ain’t Easy menu just yet, but the Neumanns look forward to putting those Two Docks beauties—the aptly named Skyway Sweets—on the board soon. Having the hatchery nearby will help move things along, says Welch.

“We’ll be able to spawn our own using parent oysters from the local environment, so we’ll be raising animals that are wired for Tampa Bay,” he explains.

Lead time is one of the challenges of the aquaculture business; building inventory with clams and oysters is a roughly 18-month process.

“But we know our leases work,” Welch says, “and we’ve been producing beautiful and really delicious oysters.”

The Neumanns are ready, as are their customers.

“When people come here, they want to eat stuff that’s from here,” Matthew Neumann says. “I’ll be thrilled to serve them.”

Did You Know?

…clams and oysters have different levels of sweetness, salinity, and other flavor notes based on what is known as merroir. It’s the oceanic equivalent of terroir—conditions in which the animals grow affect the way they taste. In some cases, oysters farmed close to one another can taste differently based on currents. Two Docks clams, says Aaron Welch III, “come up a little saltier than in Cedar Key because they don’t get as much fresh water.” It can be seasonal, too. “They’ll taste a little different at the end of the summer when it’s been raining for three months. In February, March, and April, they’re saltier.”

…a single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day, and clams five to 10 gallons, making water clearer as they clean. “Seagrass can then grow better because more sunlight penetrates,” Welch explains. “Clams will stabilize the sediment they’re growing in, which makes it healthier, not as mucky and prone to kill seagrass.”

…clams and oysters are farmed in designated areas and the practice is heavily regulated. “The State of Florida monitors our leased areas constantly and checks the water quality for toxins and harmful algae that can harm animals or consumers,” according to Welch. And when they detect red tide or similar conditions? “They shut us down.” Animals are monitored very closely until the bloom passes.

…farmed oysters are sustainable and in some cases help seed wild populations, allowing depleted beds to regenerate and maintain healthy ecosystems, keeping shores safe from storms and erosion and serving as nursery-like sanctuaries for young fish populations.