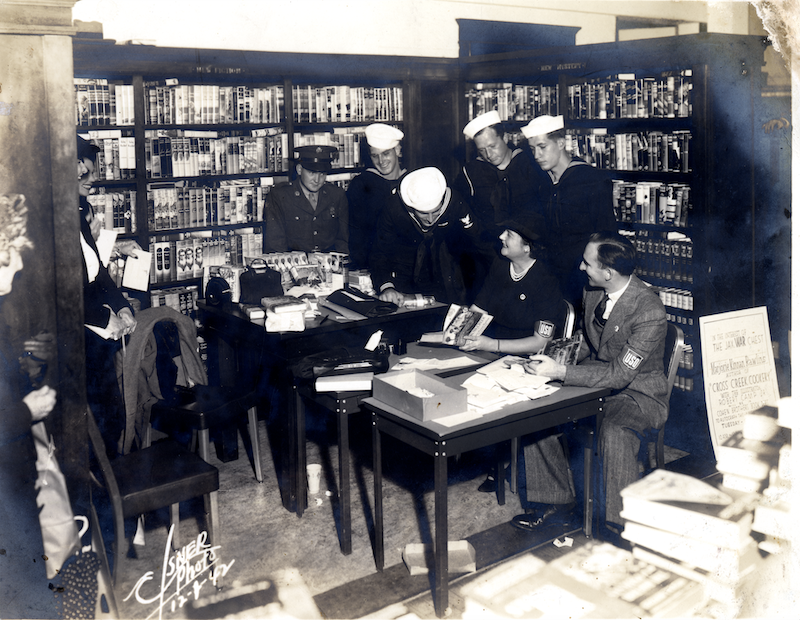

The letters of admiration came by the dozens, filling the oak-shaded mailbox of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. They arrived from everywhere the world curves—from Hawaii, from the Philippines, from Ireland and Egypt and Australia and beyond. In other words, everywhere the United States had men and women fighting in uniform in 1942 during the early days of World War II.

Earlier that year, Rawlings published Cross Creek, a moss-draped, Florida-based memoir titled by the location of her backcountry home on the eastern shore of boot-shaped Orange Lake, almost equal distance between the relative metropolises of Ocala and Gainesville.

The romantic detail that filled Cross Creek tied a homesick knot in the hearts of soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and coast guardsmen as Rawlings described life among the palmettos and hibiscus, alligators, turtles, and citrus groves.

Selected by the Book-of-the-Month Club, Cross Creek was released worldwide in the spring of 1942, only a few months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, as an armed services edition small enough to fit snugly in the pocket of a military uniform. With few ways to entertain themselves in forward positions, servicemen literally kept the book close to their heart, reading it over and over when few other options existed.

Eight out of every 10 letters written by overseas soldiers to Rawlings about Cross Creek mentioned how her talk of food in the book rekindled memories of their boyhood kitchen.

“Lady,” one wrote, “I have never been through such agonies of frustration.”

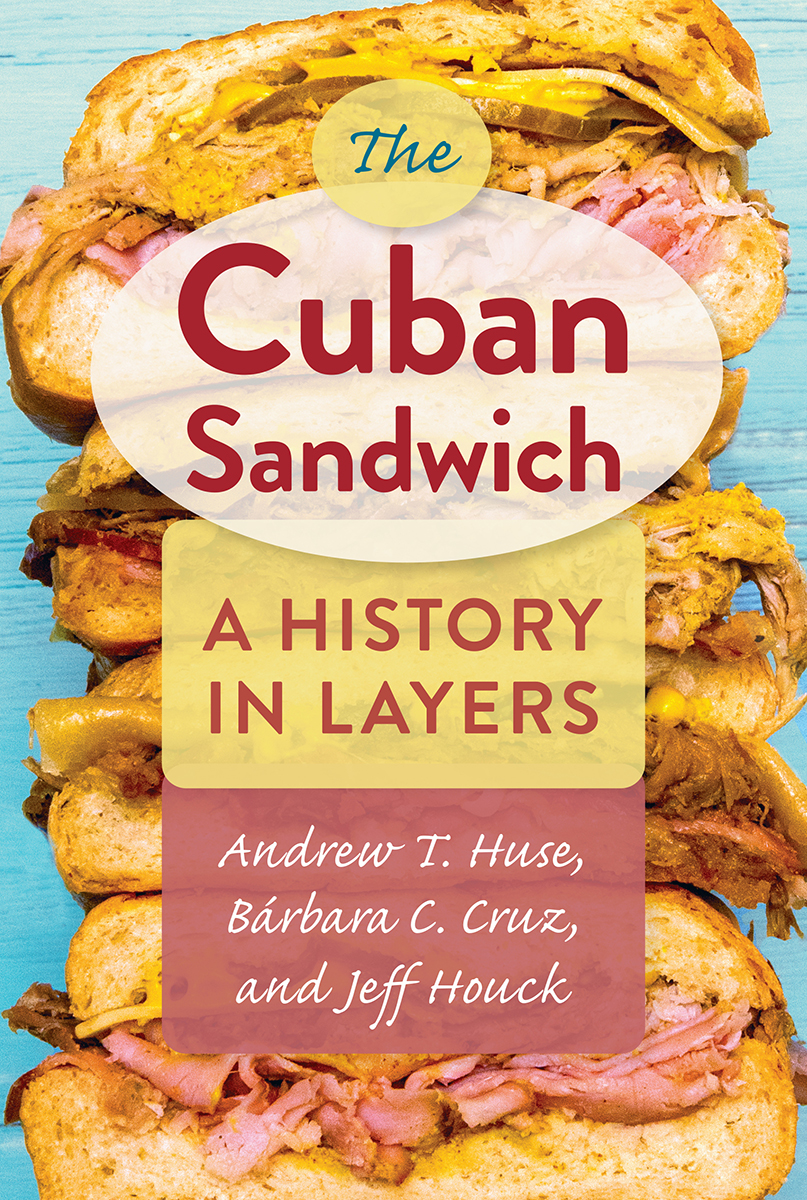

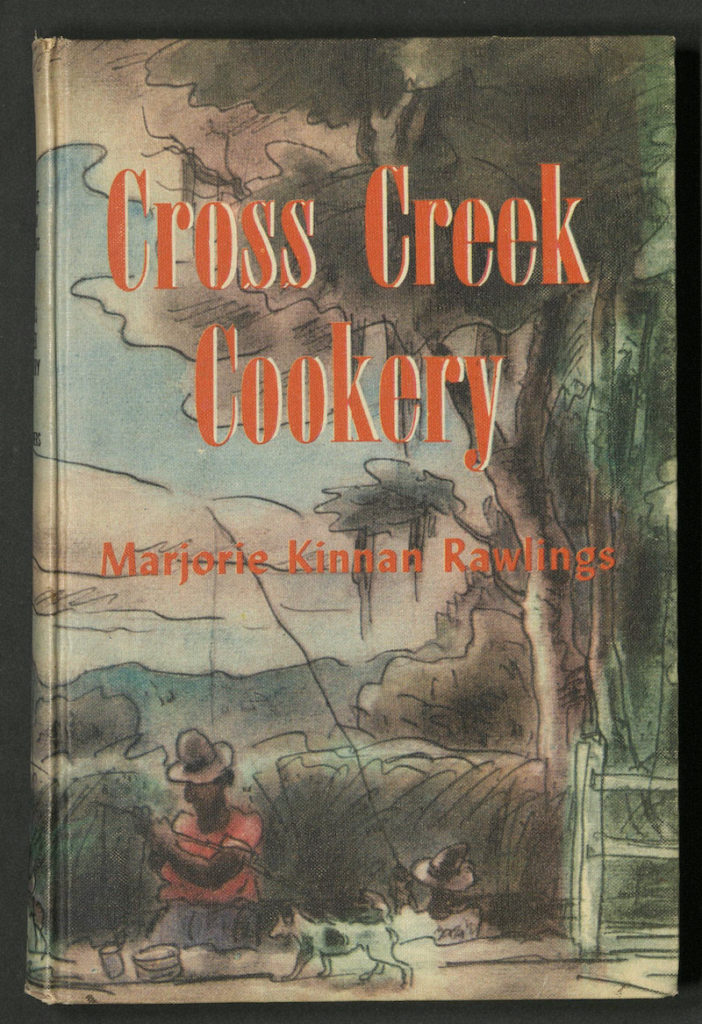

It is the business way of publishing to capitalize on success, (yes, there is an Official Harry Potter Baking Book), so her editor at Charles Scribner’s Sons asked Rawlings for a follow-up. Her response, published in time for Christmas: Cross Creek Cookery,

a 256-page collection of essays and homespun recipes that, 80 years later, is perhaps Florida’s most important and least remembered pioneering cookbook.

Each page reads like a time capsule of life long ago in north-central Florida, with recipes for creating such southern staples as biscuits and hoe cakes and cheese grits and fried shrimp mixed with dishes only someone living at that time and in that place would consider making. There isn’t much call in the Uber Eats era for entertaining dinner guests with Pot Roast of Bear, Lamb Kidneys with Sherry, or Alligator-Tail Steak. The days of serving Jellied Tongue have long passed, thankfully. But Rawlings and her Cross Creek neighbors ate those dishes by necessity more than choice. You devour what the land provides, whether it’s by shovel, by hook, or by gun. When the world gives you loquats, you make Loquat Jelly.

Cross Creek Cookery also capitalized on her great love of cooking and entertaining. A domestic chore for women of that era, cooking for friends, neighbors, and literary celebrities who visited in the wake of her success became her emotional outlet. “My recognition of cookery as one of the great arts was not an original discovery,” Rawlings wrote, “but it is as important a one for the individual woman as the discovery of love.”

That she cooked all of it in a cramped, wood-fired country kitchen—with the guidance of her Cross Creek neighbors and assistance from her housekeeper, Idella—is even more remarkable.

Early in Cross Creek Cookery, she set the wartime table for the pages that followed.

“The door of the world’s house is shut and there is no breaking of bread with the wayfarer,” Rawlings wrote. “The frustrated corporal wrote of his home and of his family. It was not only the squab-sized chickens stuffed with pecans, the crab Newburg … for which he longed, but the convivial gathering of folk of good will.

“Country foods, such as those of Cross Creek, have in them not only … butter and a dash of cooking sherry, but the peace and plenty for which we are all homesick.”

To merely call Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings an author ahead of her time is to understate her pure and complete badassery given the context and complexity of the times during which she lived.

Born in 1896 and raised in Washington, D.C., Marjorie Kinnan wrote prize-winning short stories as a young schoolgirl and later attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where she graduated with honors.

It was at university where she met writer Charles Rawlings while both worked on the school literary magazine. They married in 1919, later moving to Louisville, Kentucky, where she wrote for the Courier-Journal newspaper. A few years later, they moved to Rochester, New York, where Marjorie wrote for the Journal, including a column of poetry she started in 1926 called “Songs of the Housewife” that proved popular enough to appear six days a week. Topics included baking, dusting, envy-inspiring people who finish Christmas shopping long before the holiday, and the horror of having company arrive with nothing prepared to feed them.

Connie May Fowler, author of Before Women Had Wings, described a 1997 collection of the columns as, “A fascinating tapestry woven from the lives of women who had won the right to vote a mere six years earlier. … We hear the voice of an emerging feminist, a voice that stubbornly and—given the political climate of the 1920s—courageously insists that women be respected.”

In 1928, tired of the life they were living, the couple sold their possessions and Rawlings took a small inheritance from her mother to purchase a 72-acre orange grove about five miles southwest of Hawthorne, Florida. The acquisition included two cows, a few mules, 150 chicken coops, two chicken brooders, a raft of farming equipment, and a dilapidated Ford truck.

The bold move was prompted by dissatisfaction with life in Rochester and a need to broaden from their freelance opportunities, said Ann McCutchan, author of The Life She Wished to Live: A Biography of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. The couple had visited a brother of Charles who ran a gas station. Marjorie, who despised cities, fell in love with the challenges brought by rural living. In Florida in the 1920s, the discomforts were as plentiful as the citrus that hung like droplets from the trees.

“Charles loved boating, and they were just smitten with going out on the water,” McCutchan said. “She loved hearing about the hunting. It was all very exotic to them. They needed a change for lots of reasons. They decided to jump off a cliff and imagined they would support themselves by selling oranges.”

With the farm came a wood-shingled “dogtrot house” built in 1884 that needed immediate repair. (The architectural style was so named because of a breezeway that connects two adjacent homes.) She planted a garden right away so that they would have vegetables on the table. A dairy cow supplied milk. Rawlings, who once said she felt such a connection to the land that she felt its vibrations, made friends with her wary neighbors, learned to hunt, and went off with buddies in search of local game far more often than did her husband.

“She just loved to go out,” McCutchan said. “She didn’t care about killing anything. She just liked to be outdoors.” Not only was raising and capturing their food necessary for subsistence, it allowed her to delve into the culture. It’s difficult, after all, to properly describe how to cook a turtle in a novel if you’ve never done so.

“They weren’t going out to Publix,” said Florida author and retired journalist Eliot Kleinberg. “They were shooting their own food and growing their own vegetables. The nearest grocery would have been an hour away in Gainesville or Ocala. She was very much a self-reliant individualist.”

Rawlings began writing short stories after filling her notebooks with details of wilderness life. In 1930, Scribner’s published two of the tales, but financial success still was far off. In 1932, tired of a struggling life in the Florida scrub, Charles left and they divorced. Marjorie had no intention of leaving. Her editor, Maxwell Perkins, suggested that her voice as a writer was strongest when telling stories of her life in Cross Creek.

Her first novel, South Moon Under, was published in 1933, telling the fact-based fictional tale of a young man who sells moonshine to make ends meet. The book was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize.

Rawlings found enormous success in 1938 with her novel The Yearling, a heartbreaking story of a Florida boy’s relationship with his father that centered on the child’s fondness for a young deer, despite the setbacks the animal causes the family. Originally intended to be a story for young readers, The Yearling was selected for the Book-of-the-Month Club and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1939.

In 1941, she married St. Augustine hotelier Norton Baskin, dividing her time between their home in Crescent Beach and her Cross Creek retreat.

Staying with the theme of life in a rural Florida hammock, her memoir Cross Creek about living adjacent to a natural waterway connecting Lochloosa Lake to Orange Lake, published in 1942, becoming a classic piece of American literature.

In 1946, a film of The Yearling starring Gregory Peck became MGM film studio’s most successful movie of the year, winning three Academy Awards. Footage captured at Rawlings’s home in Cross Creek was used in the film. The Yearling fueled the rest of her career, making the area around the Rawlings homestead a destination that continues to be popular eight decades later.

For the millions of readers raised on the vivid fiction of The Yearling, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s real-life experiences detailed in Cross Creek cleared any questions about how much of the novel was based on fact: nearly all of it. Cross Creek Cookery confirmed it all even more so with flavors from the Creek for readers to try in their own homes.

Cross Creek describes her life among the five white families and two black families living on a bend in a country road along a creek. Drama throughout the book expands from that rugged environment, from the work of managing the orange grove, from battles with runaway pigs, and from a series of unruly farmhands. “Rawlings describes her life at the Creek with humor and spirit,” her publisher said. “Her tireless determination to overcome the challenges of her adopted home in the Florida backcountry, her deep-rooted love of the earth, and her genius for character and description result in a most delightful and heartwarming memoir.”

It’s a description that does nothing to address the basic realities and lack of comforts for her at that time. Whatever she had while living in the north did not exist for her as a southern bride. For example, when she first “came to the Creek,” Rawlings wrote, “I had for facilities one water faucet in the kitchen, a tin shower adjoining the shed and an outhouse.” In weather cold enough to freeze her bird baths solid, the outside shower “was a fit device for masochistic monks.”

That house and those facilities still exist at what is now the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings State Historic Site. The eight-acre park is open every day and interior guided tours of the farmhouse are available Thursday through Sunday, except during the months of August and September for maintenance. You can wander through the sitting parlor and bedrooms, see the spot where she dispatched pigs that had trashed her garden. There’s a replica of her barn, and a small bed in the bedroom wing where Gregory Peck stayed while exteriors were shot during filming of The Yearling. The adjoining lawn is home to a variety of citrus trees and poultry cluck their way around the yard, dodging visitors.

The house and surrounding land is 120 miles as the crow flies from downtown Tampa, or almost two hours of white-knuckle driving on Interstate 75 and a handful of back roads. In the 1940s, it would have taken you the better part of a day to make the trek on what passed for state roads, if your vehicle didn’t break down on the way and if, during wartime, you had the gasoline rations to make the trip. More than likely, you instead would have ridden a spur of the Seaboard–All Florida Railway, which had a depot at Citra, less than seven miles from Cross Creek. These days, Citra is home to the kitschy Orange Shop, a family-owned roadside attraction that sells honey, jellies, and “marms.”

In January, when skies are a cloudless cobalt and temperatures are moderate, you can imagine the home as a writer’s Shangri-la. Today, a replica Remington typewriter resides on a wooden table—along with a crystal ashtray and a pack of Lucky Strikes—situated on a screened porch that allowed her views of the grove as she wrote.

In cold weather, meals were eaten in the farmhouse dining room with its open fireplace. If there were guests, they likely dined in the living room “looking through the French windows out across the veranda to the fresh leafy world beyond.”

In August, only the breezes off Lochloosa Lake from afternoon squalls keep the open-air homestead tolerable. It’s why she kept a bed during the hottest months only a few paces from the writing table. Any breeze was better than nothing.

The kitchen, with a view of her bountiful fenced garden, was where Rawlings was happiest making the most of what she could grow. Volunteers continue to maintain the garden to keep it producing greens and vegetables and beans during growing seasons.

“Only vegetables that are a spécialité du maison at Cross Creek” made it into Cross Creek Cookery. Broccoli a la Hollandaise and Carrots Glazed in Honey would satisfy at modern tables. Beets in Orange Juice might not be as widely accepted. The recipe for Okra A La Cross Creek does its best to disguise the slimy nature of the seed pods. (She recommends serving 12 okra pods per person.)

Rawlings’s dry humor adds a literary umami flavor to Cross Creek Cookery, frequently in subtle ways. The 58-page chapter on desserts—the largest in the book—showcases perhaps her most famous dish, “Utterly Deadly Southern Pecan Pie,” but it doesn’t appear until 30 pages after the section’s intro. And then, she almost begrudgingly includes it.

Made with four eggs, a generous amount of southern cane syrup, “broken pecan meats,” sugar, butter, and vanilla, she acknowledges the intensely sweet treat’s appeal, especially to men. She then follows it with a recipe for “My Reasonable Pecan Pie.”

“I have nibbled at the Utterly Deadly Southern Pecan Pie, and I have served it to those in whose welfare I took no interest,” she writes. “Being inclined to plumpness, and having as well a desire to see out my days on earth, I have never eaten a full portion.”

Intrigued, I made the pie one night at home after tracking down the cane syrup. She wasn’t wrong; the intense sweetness almost brought me to my knees. But what she omitted from the description was that the aroma from the baking was so pungent and perfect, I didn’t want to leave the house for a week. Every whiff was like enjoying a fresh slice.

The current version of the home’s kitchen, complete with a wood-burning stove with a white enamel front, a horseshoe-shaped pantry that fills with afternoon sunlight, and yellow gingham curtains, is a replica rebuilt according to the specifications of Idella Parker, whom Rawlings described as, “the perfect maid.”

Parker used the phrase as a somewhat sarcastic title of her tell-all book about her time in service to the author and her famous friends from 1940 to 1950. “Let me say right off that I am not perfect, and neither was Mrs. Rawlings, and this book will make that clear to anyone who reads it,” Parker wrote. “Mrs. Rawlings was one of the kindest persons I have ever known, but she could also be very hard to get along with and impossible to reason with at times. In other words, she was a human being, with human faults and troubles, and so am I.” Well-educated and remarkably patient, Parker eventually tired of Rawlings’s volatile moods and alcohol intake as she got older.

But for the years she worked at Cross Creek, Parker clearly had an influence on Rawlings’s already considerable culinary repertoire. Foodways and recipes from other black families who lived nearby also left their imprint, so much so that their friendship through food expanded Rawlings’ already liberal views of racial equality.

And when Zora Neale Hurston came to visit, the contemporary Florida author was invited to stay in the main farmhouse at a time when segregated quarters were the norm in the South.

“She was progressive for her times, but her times were not progressive,” Kleinberg said.

To Rawlings’s credit, she notes in the book when recipes come from another source, specifically Idella’s Crisp Biscuits. They lean heavy on the Crisco or butter and were encouraged to be devoured hot with a melting dab of butter. She wrote, “Men love them, but are likely to be embarrassed by them, as they are ashamed to keep asking for them. I always say, ‘Oh, take several,’ and keep a plate on the table.”

At a time when society was cruelly unequal, food was a binder between neighbors. Cooking provided a common thread that reminded the cook as well as the eater of the humanity of all.

“Food imaginatively and lovingly prepared, and eaten in good company, warms the being with something more than the mere intake of calories,” Rawlings wrote. “I cannot conceive of cooking for friends or family, under reasonable conditions, as being a chore.”